Incredibly, it’s the 40th anniversary of the launch of the legendary Sinclair ZX Spectrum. April 23rd 1982 was the day upon which Sinclair’s home computing dream hit home, creating millions of head-turned, new believers.

If you’re familiar with the Spectrum (perhaps having tensely eyed the 12+ minute loading time of The Hobbit, or worn the lettering from the L key due to too much Jet Pac) then round about now you’re probably feeling a little… legendary too…

Yes, it’s 40 years.

And what a 40 years. The groundwork that Sinclair put in place, for what for many was would be their first brush with computing, laid the foundations for so many innovations and inspired so many future pioneers, that the modern internet, mobile computing and the future metaverse all have direct lineage back to Sinclair’s creations.

Be under no illusions. This is a big deal.

Sinclair starts here

Sinclair itself was the creation of Clive Sinclair (becoming Sir Clive in 1983 on the back of 1982’s stellar Spectrum success) whose obsession with transistorised miniturisation (and angular black industrial design) began with Sinclair Radionics work in the field of hi-fi, producing miniature hi-fi amplifiers in 1964 and “the world’s smallest radio” the Micro-6 in 1965.

While the embrace of electronics and their new-found ability to reduce the size of products was welcome (in an age where amplifiers and the like still contained large, expensive valves, giving off as much heat and light as they did music power) Sinclair’s designs always skirted the realms of what was actually possible, giving their products a reputation for style over substance right from the outset.

Yeah, this was great… But too ‘great’?…

Branching out of multiple refinements of their amplifier and audio business, a smash hit Sinclair Executive calculator (the first truly ‘pocket calculator’) followed in 1972. However, the Black Watch digital watch in 1975 proved to be a step too far, being unreliable and difficult to manufacture due to its extreme design, tight price point and limited availability of the new tech inside.

Never let it be said that Sinclair ever had an easy ride to greatness.

A bodged attempt at a pocket television followed and – in a pre-cursor to the confusion, rebranding and final fizzle-out to come – Sinclair had the assets and tech associated with the Radionics brand passed from owner to owner, allowing Sinclair to evade bankruptcy and leave his own company with a £10,000 golden handshake… but actually achieve little else.

Kickstarting the computer age

Good news though, Sinclair had spent the final two years at Radionics creating a new company ready for its demise and his departure, undergoing multiple name changes and producing a surprisingly popular computer kit based on the breakthrough National Semiconductor SC/MP CPU. The MK-14 sold for the ridiculously affordable price of £39.99 in 1977, setting the scene for Sinclair’s legacy.

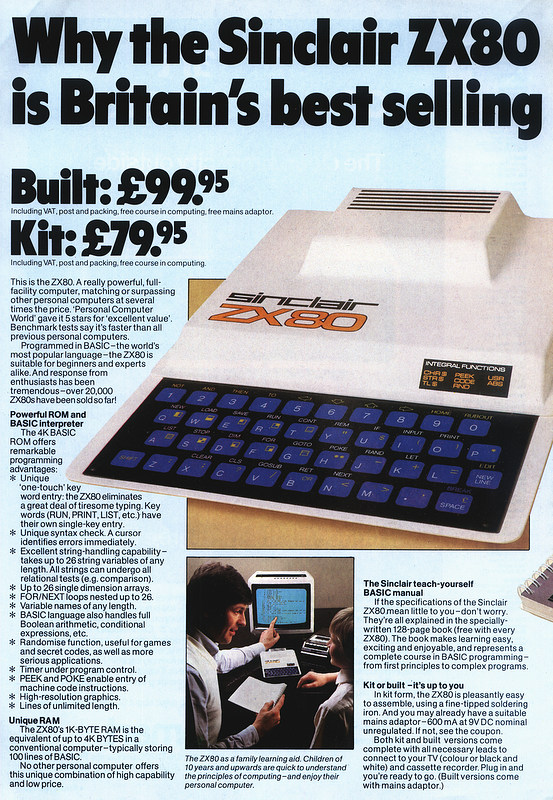

The ZX80 – released by the newly-named Sinclair Computers Ltd – was arguably the first genuine ‘home computer’ being both designed for and marketed squarely at the home consumer market. However, thanks to its inevitable Sinclair styling its low profile looks, flat membrane keyboard – a minor step up from the same cheap solution used on the MK-14 – and bulging lid made it more akin to a Lotus Esprit (the star of 1977’s Bond classic The Spy Who Loved Me) than a computer. Nevertheless it became a curious talking point as it loomed enticingly from the pages of every Sunday supplement all through 1980…

“Just what was a ‘personal computer’ anyway,” pondered a nation…

The simple, single board design and non-reliance on costly monitors – the ZX80 instead featured a TV modulator so you could plug it into the aerial socket of any TV – had allowed him to bring the machine in at an inconceivable £99.95. And there was even a £79.95 kit version for those brave enough to put the thing together themselves. ZX80s shifted from the outset and soon 50,000 were sitting with owners who perhaps had little idea as to what to do with them.

The best gets better

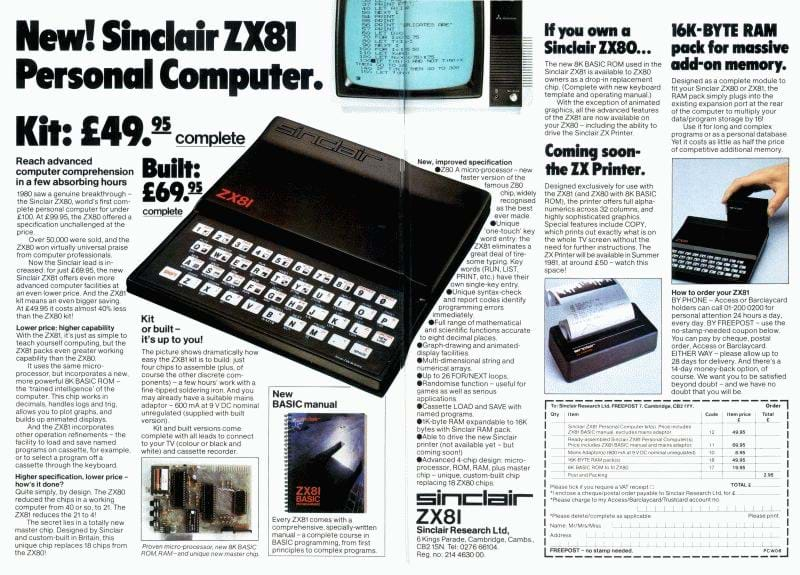

1981’s ZX81 followed, simplifying the chipset from 21 chips to just four and upgrading the 80’s video output. Incredibly, the ZX80 could either run its modulator (and produce a picture) or read its keyboard and register a keypress, meaning that every time you pressed a key the screen went blank… Not ideal if you’re planning on playing a video game… The ZX81 righted the wrong with a ‘slow’ mode able to distribute the processor’s time more evenly, thus a new era was born…

Available at an even more affordable £69.95 built and £49.95 kit it even came with options such as its 16K RAM pack supplementing the miniscule 1K on board to something able to run a half decent program. And while all the talk was of ‘helping the kids with their homework’, ‘Dad doing the accounts’, or ‘Mum filing her recipes’ pretty soon more and more games began to fill the shelves…

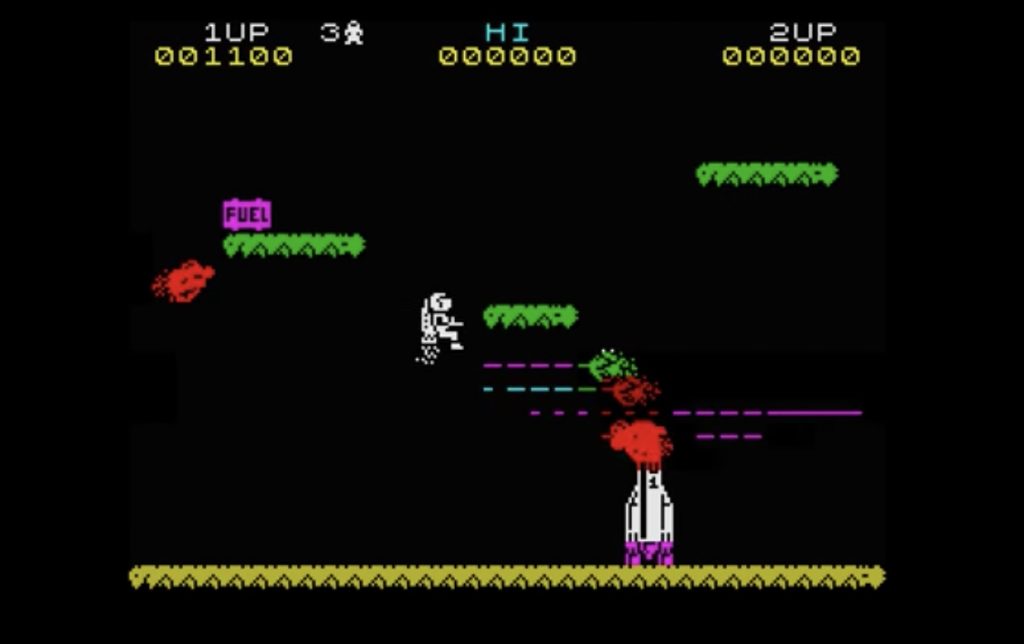

The UK’s 80’s gaming boom and the machines, games, names and fortunes it made is a whole other story, suffice to say that it was games that turned out to be the real driver of the ‘microcomputer’ boom. Shops previously trying to shift expensive IBMs, Olivettis, Apricots and Apples soon changed tack and instead lined the walls with hundreds (thousands?) of cassette tapes, each promising experiences beyond the imagination… In pixelated black and white…

Now in living colour

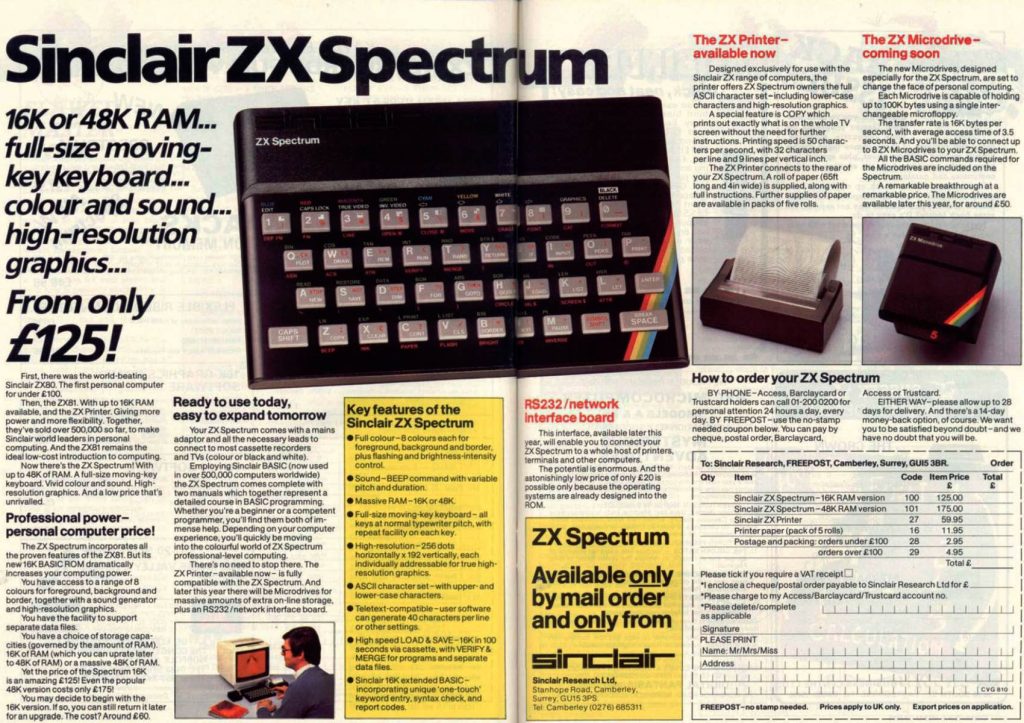

Thus the scene was set for the ZX81’s successor. Codenamed the ZX82 (obviously) its big step up would be to provide not only an increased screen resolution (up from 64 by 48 pixels to 256 by 192) and sound (incredibly the ZX80 and ZX81 were completely mute) but colour graphics too.

With Sinclair’s mantra of ‘keep the cost down’ booming in designer Rick Dickinson’s ear, he once again produced a device that fitted the brief perfectly in that a) it looked barely fit for purpose and b) was needlessly far smaller than anyone required. Again, a crude, naked edge-of-the-circuit-board expansion port was visible, there were tiny connections for that essential cassette recorder for loading and saving programs, and a TV modulator output, this time delivering glorious colour.

Over months of ownership, inadequately heat-sinked cases would warm up and cool down, weakening the feeble bond between plastic case and thin, metallic, rainbow-striped upper, which would literally begin curling up at the edges…

The only new Spectrum hardware of note would be the its tiny tinny speaker. The Spectrum cut costs by outputting the sound from what was barely a buzzer inside the machine rather than incorporating audio as part of the modulated output (a move that seems ludicrous today). Then there was THAT keyboard…

Type of the living dead

Ah, the Spectrum keyboard… The Spectrum toted “a full-size moving key keyboard with all keys at typewriter pitch” according to the ads… In actuality the Spectrum foisted a field of lumpy rubber nuggets with all the appeal of grey alphabetti gnocchi…

Its infamous ‘dead flesh’ feel fell easy prey to all of the Spectrum’s competitors. The Vic 20, BBC Micro, Acorn Electron, Elan Enterprise, Amstrad CPC, Dragon 32 and arch enemy Commodore 64 ALL had REAL full typewriter keyboards and all made a big play of it. In actuality however, Sinclair was right. No-one gave a stuff about actually typing on the thing. Just tell us which one is the fire button…

And it shifted in its millions. In fact, including spin-offs (more later), over 5million of the things found homes, being especially popular in the UK and – thanks to sharing the same PAL TV system – Spain, meaning that Sinclair could import them unmodified. (Elaboration: Spain actually used PAL-BG meaning that modulated audio was incompatible, a problem for the competition that the Spectrum totally sidetracked ‘thanks’ to that built-in speaker.)

And with millions of installed users, which easy-to-learn machine are the upcoming wave of new, masterful games programmers going to develop for? Thus from ‘82 to ‘85 companies were founded, names made and fortunes minted as games shifted for £4.99 to £7.50 and even the occasional £14.99…

Bug-Byte, Quicksilva, Hewson Consultants, Melbourne House, Software Projects, Ocean, Microsphere, Psion, Imagine, Ultimate Play The Game, Codemasters… All pumping out legends like Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy, Ant Attack, Quazatron, The Hobbit, Horace Goes Skiing, Daley Thompson’s Decathlon, Arcadia, Jet Pac, Schooldaze, Dizzy… From Andrew and Philip Oliver, Tim and Chris Stamper, Matthew Smith, Andrew Hewson, Rod Cousens, Eugene Evans… We could go on…

Which – inevitably – begins to beg the question ‘Where did it all go wrong’? After flying so high and being so pivotal in creating new paradigms of entertainment and culture, how exactly could Sinclair screw up its next steps so completely?

Perhaps it’s just a simple continuation of their boom-then-bust story to date, but Sinclair entirely, and incredulously, failed to capitalise on the massive success of the Spectrum.

Spectrum sequel y’say? Nope…

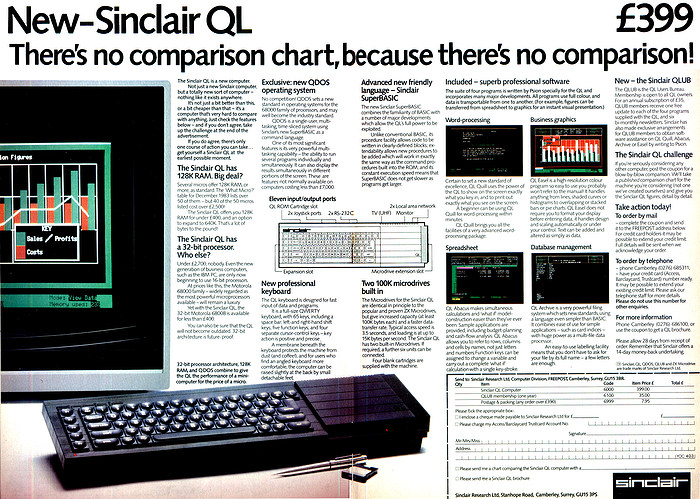

Rather than deliver a true sequel – ideally a 16-bit machine to rival the new tech coming from Atari (ST) and Commodore (Amiga) and huge leaps in the console field from Sega (Master System to Megadrive) and Nintendo (NES to SNES) – Sinclair instead ploughed money and energy into the Sinclair QL – a pricey-at-£399, 8-bit/hobbled-16-bit, ‘business’ machine that literally nobody wanted. With an awful keyboard… In a design that was too small for its innards… With an OS and processor that left games devs cold… That didn’t even feature an on/off switch.

Instead – at the consumer end of Sinclair’s afterthoughts – we got 1984’s Spectrum+, a Spectrum in a QL-like case… and little else. Then 1985’s Spectrum 128, a machine actually developed by a Spanish business partner for the Spanish market after Spain’s government levied a tax on computers with under 64K and necessitated Spanish characters on keyboards. (At least the sound came out of the TV this time.)

No, really. It gets worse

And if 1984’s QL was Sinclair steadily climbing the gallows then their 1985 electric ‘car’ – the C5 – was them popping on a noose and flinging themselves from it. Yes, it’s hard to believe, but immediately after inventing and totally aceing the home computer revolution, Sinclair tried to flog us a £399 deathtrap tricycle driven by a washing machine motor*. (* OK, it was a truck radiator motor… That only drove the left-rear wheel… We could go on…)

Thus Sinclair was doomed. Fortunes and hair were lost, reputations ruined and Sinclair’s marketing and merchandising were snapped up for £5m by rivals Amstrad. Still, that at least would give us the Spectrum sequel we all wanted?

Wrong. 1986’s Spectrum+2 turned out to be a cross between the Spectrum and their own rival CPC machine. Next came 1987’s Spectrum+2A, a beneath-the-hood cost cutting exercise. Then – also in 1987 – the Spectrum+3 which featured a disc drive and other hardware ‘improvements’ NOT including a processor upgrade and which rendered some classic software incompatible. [puts revolver to temple]

There were even +2Bs and +3Bs in there somewhere… But the less said, eh?

Instead let’s remember the good old days, raise a glass of English sparkling and toast the 23rd of April 1982. When the Sinclair Spectrum was launched. When a nation’s teenagers flipped from barely knowing what a computer was, to wanting one for Christmas. When the doors to the future were finally flung open and this whole crazy, wild ride really began.

Sinclair ZX Spectrum. Thanks for the memories, and here’s to the future you created.

We asked a few Spectrum fans, past and present, for their 16 and 48K memories:

Matt Bielby

“Rather embarrassingly, I remember not being too impressed the first time I played a Spectrum game. But I learned to love and appreciate it. It was cheap, it was everywhere, it was relatively easy to use and understand, and it encouraged a just-have-a-go attitude to programming and game development – almost a punk home computer system, if you like. And it seemed to attract funny, eccentric, inventive – and very British – fans and game creators, all of which I love.

Publishing legend and magazine editor, Your Sinclair, Super Play, Amiga Power, PC Gamer, .net, Total Film and more

“Sadly, the Spectrum always seemed destined (or doomed) to be a one-off – Sinclair never felt like a company that had it in it to create a dynasty of products, like a Sony or Nintendo or Apple. But what it did do was inspire us to be creative, to use our imaginations, to enjoy being the slightly wobbly but feisty underdog. (It’s no accident, I think, that one Your Sinclair T-shirt we did remains especially fondly remembered – “It’s crap! (In a funky skillo sort of way)”. It was a legend as relevant to the computer as it was to the magazine.)

“When I think of the Speccy now, I think of games like Jet Set Willy and Knight Lore and Cybernoid, but mostly I think about how accessible and adaptable it was, and how it encouraged such an amiable but anarchic do-it-yourself attitude. And how it gave so many people access to technology they could never have afforded otherwise. Really, I adored it; it had soul.”

Philip & Andrew Oliver

AKA The Oliver Twins, game development legends, creators of the Dizzy series and countless classics, founders of Panivox, creators of RichCast

“The Spectrum launch in ’82 roughly coincided with our first making games and was very exciting. We saw it as amazing technology since we were on the ZX81 with just 1K memory, black and white blocky graphics and a ‘paper’ keyboard. We were making and selling games but it wasn’t until October ’86 that we created Super Robin Hood – on Amstrad CPC – for Codemasters and sales exploded that David Darling, co-founder of Codemasters gave us a Spectrum and said please port Ghost Hunters, to the Spectrum.

“We thought this was a little bit crazy as we really missed the boat on the Spectrum, this was over 4 years after it launched! But we figured that we’d give it a go and found it only took around a week to convert. The Amstrad internal design is very similar to a Spectrum – some might say ‘copied’ and enhanced a little. It was while writing Ghost Hunters came up with the Dizzy concept and in the following spring that we released it.

“Over the next few years we did all our games on Amstrad and Spectrum and released 27 Spectrum games, many of which became best sellers. We’re pretty sure that makes us the most prolific Spectrum game developers in the world! A few years ago, we even created the full design for the Wonderful Dizzy for Spectrum too – developed by some wonderful Dizzy fans.

“Looking back on the Spectrum it really was a computer that was more of an electronic toy for the masses, particularly in the UK and several countries around Europe. It even spawned many Russian clones. It’s a sad truth that while techy while teenage boys in the 80’s idolised Sir Clive Sinclair, he himself didn’t like the Spectrum being used for games and, in fact, actively worked to make the sequel, the Sinclair QL, more of a business machine which was a real shame.

“One legacy of the Spectrum is that it helped inspire so many young people to learn to program and go on to become the core of the UK games industry. Many of those people now hold high positions in today’s games companies creating tomorrow’s interactive entertainment, including the metaverse.”

Rana Rahman

“The first time I clocked the Speccy was in WHSmith or John Menzies sometime in 1984 (I can’t quite recall, it was nearly 40 years ago!). Jet Pac was on display, boasting an incredible feat of software engineering and creativity. I marvelled at its silky smooth graphics, and wondered just how those Ultimate Play The Game wizards managed to squeeze arcade quality graphics out of such a tiny box. Hence began the campaign to get a Spectrum for Chrimbo…

Founder of video games, media and Web3 comms co. Raptor PR

“The Spectrum changed my life and destiny and I jumped head first into the world of gaming. It was so new and exciting. It transported me into different worlds. It encouraged me to use my imagination. Nothing quite compared to it. Not sport. Or TV. This was ‘interactive entertainment’…

“I didn’t care about coding. For me, it was all about the games, the dev stories seeded by the games media, and voraciously absorbing as much info as I could via gaming magazines. Gaming culture was brand new back then so discovering it made me feel part of a new emergent community, whilst most people – including my parents – didn’t quite understand it. And at school, all my best friends were kids who loved gaming.

“Starglider, Carrier Command, Renegade, Robocop by Mike Lamb… And a plethora of Ultimate Play the Game titles including Jet Pac, Pssst!, Gunfright, Knightlore, Underwurlde, and Lunar Jetman. I recall being horribly letdown by Ocean with its much delayed Knight Rider game. I’d incessantly call up their Manchester office, and ask for release dates!

“It’s almost impossible to accurately quantify just how much of an impact the Speccy has had on gaming today. It massively impacted a whole generation of UK talent from coding, to gamedev, to hardware design, and even PR! It’s this lifelong passion which started in the early 80s on the Speccy that still resonates today. I firmly believe that my clients, journalist friends and prospective clients at Raptor PR can still see this burning passion and pride for the games industry, and that many of the modern architects of the metaverse started out on the ZX Spectrum.”

Kelly Vero

“The Spectrum 16K is the sole reason I am here. It gave me wings so I could fly, it gave me dreams that I could achieve and it gave me friends outside of the flimsy motherboard, flashing graphics, load dit dits and clanky handshaking that somehow made the most recognisable tune on Earth.

Futurist, game developer and metaverse architect

“From Horace and the Spiders and Jet Pac to Manic Miner and Cookie: we waited, constantly, we lived through every permadeath and we dusted ourselves off and did it again every day until our folks shouted us down for dinner. Thank you Sir Clive of Sinclair for the best years of my life.”

Sam Dyer

“My two best friends had a Spectrum and an Amstrad CPC, and I had the – [ahem] – Commodore 64… We would spend hours at each other’s houses playing games. It was such a magical time, and one that I look back on with so much nostalgia. I’ll never forget the first time I heard the ZX Spectrum loading! That sound! My friend would load games from his hi-fi stack in the corner of the room, and his dog would keep knocking out the cable that was draped across the room…

Graphic Designer and founder, Bitmap Books, creator of the definitive Spectrum book, Sinclair ZX Spectrum, A Visual Compendium

“Many happy days were spent on Powerboat Simulator, Treasure Island Dizzy, Bounty Bob Strikes Back, Chuckie Egg… Although I’ve always had a fondness for the Spectrum, it wasn’t until I curated and designed our third book that I truly appreciated how groundbreaking the Spectrum was.

“Superstar programmers such as Peter Harrap, Jim Bagley, Tim Stamper and David Perry all cut their teeth on it. It single-handedly kickstarted the UK gaming industry – not bad for a system with 16K of RAM! Happy birthday to the ZX Spectrum. It’s just a shame that Sir Clive isn’t still with us to enjoy such a milestone.”

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the world's biggest entertainment, home and tech media brands. He's reviewed all the greats, interviewed countless big names, and reported on thousands of releases in the fields of video games, music, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors, garden design and more. He’s the ex-Editor of PSM3, GamesMaster, Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes fun things for great websites.