Games have always had a difficult relationship with fashion. As games have grown up and become more mature, the fashion of player characters in games may be accused of being more about identity than narrative. As workflow and tools make fashion games easier, the unique relationship between games remains strained at the best of times.

Let’s blast a few myths and explore a few examples of where fashion meets games with the most powerful results.

The More You See, The Less You Are Seen

Henry David Thoreau, a name you don’t really hear associated with videogames or fashion, once said that, “It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.” If the first example of looking at character aesthetics in games is Pac-Man, what are we actually seeing? A world of colour against the darkest canvas. Bringing the player into the world of Pac-Man directly and presenting the ultimate problem: how to solve a problem like integer overflow.

But seriously, this was the 1980s and that’s how videogames behaved. These mostly colourful platform/puzzlers such as Frogger, R-Type, Tetris, Zaxxon and Gauntlet along with Donkey Kong, drew the player directly into the game. No-one knew or cared about how they looked.

From the mid-’80s, late-’80s, right through until the ’90s, games started to become a little more aware of themselves: focusing on pure narrative, games such as the Legend of Zelda, Street Fighter, and even Super Mario Bros 3 started to become more focused upon the protagonist, their backstory and their appearance. So that players started to select characters based on how they looked as opposed to simply being in the centre of the action, where they were before.

Tomb Raider (1996) and Final Fantasy VII (1997) demonstrated sophistication: the look and feel of these characters had come a long way in just 17 years of commercially available videogames. Was this phenomenon driven by technology? It’s the strongest motivator. Yet the unique relationship between fashion and games comes into focus from this point onwards. But why? Of course, there were many games of this era that feature incredible costumes of staggering proportions, from Zero Wing in 1989 to Tekken (1994).

Heaven Is A Halfpipe

By the end of the ’90s, 3D had become the King (or Queen) of games; the growth of console purchase – and therefore development – along with the rise of 3D graphics cards forced game developers to take aesthetics totally seriously – not just characters and protagonists, but everything from environments to non-playable assets. And with artistic freedom (thanks to technology) comes weird and wonderful characters that belong inside the gameworld. All crying for identity, all begging for style and individuality, just like their players. This results in the possibilities of escapism. Let’s face it, given half a chance all of us would be on the next plane out of here and directly into Hyrule, Midgar, City 17, and even Rivia (though that wasn’t around then… except it was).

This artistic freedom gave artists in games even more of an opportunity to drive the agenda further forward into aspirational design – the idea of coveting a pair of FemShep Boots today isn’t entirely accidental by design. But the ’90s was just getting started: the influence that games had on what we wore from 1990-1999 and vice-versa was pretty cataclysmic.

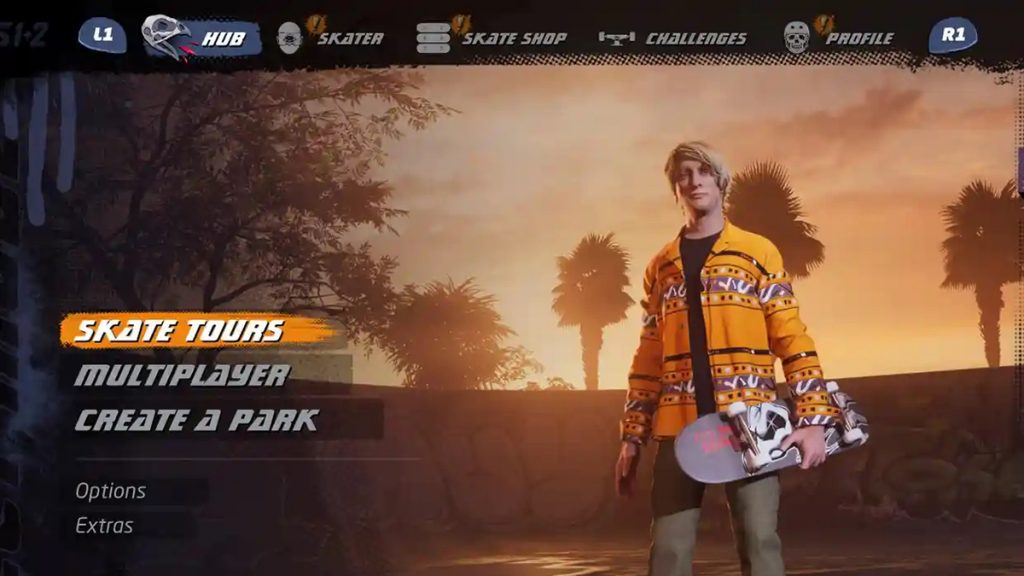

Stepping onto the runway with ease (for the ’90s) is Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater. This wonderful example of late ’90s fashion awareness is absolutely everything, isn’t it? After all, it’s impossible to expect everybody to dress in a tight white vest and a pair of combat shorts, with that hair in braids and the biggest pair of triangular boobs you’ve ever seen this side of Derby, for the rest of their lives. In Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, we have an opportunity to have the selection of a number of customisable assets and items, which include branded goods.

In one of the previous Beyond Games Checkpoints, John McCarthy explains how the rise of product placement has developed in videogames over the last 30 years and beyond. The same goes for the role of fashion inside games but this is more evolutionary than purposeful. It relies heavily on their guiding principles in character fashion design than anything “normal”. The creative director of any videogame, if you’re lucky, knows exactly what they want the character to purchase with in-game or hard currency. After all, wearing a Thrasher t-shirt and riding Toy Machine decks for somebody playing Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater suggests that to be the best, you have to look the best. This isn’t an accident; this is cultural.

Big In Japan

Japan is very self-aware; its videogame output especially proves this theory. A country made of some of the best videogame developers, artists, and designers in history never seems to put a foot wrong from the ’80s through the ’00s to today; Japanese games continue to be sartorially perfect. A country that emphasises its culture as a cynosure of entertainment and immerses its people into videogames, anime, manga, and edge technology from a young age. It’s easy to see how we have both embraced and dissected the Otaku culture for our own aesthetic purposes.

Working not too far away from Akihabara in the late ’90s, it was impossible to walk between electronic shops without falling into a cosplay café. And it is because of this assimilation of pop culture, games and obviously fashion that we can identify ourselves in videogames, manga, and anime. Ask anyone of this generation who they will cosplay as, and the answer will seldom surprise you because it reflects their personality both perfectly and imperfectly. But how that phygital experience spills into fashion is interesting in Japan because it never really emerges from that pop cultural phenomenon.

For example, Yohji Yamamoto is not entirely influenced by Hatsune Miko, for example. But the streetwear industry in Japan, being heavily influenced by Rei Kawakubo (Comme des Garçons) or Vivienne Westwood, has found itself into Harajuku which does find itself inside videogames. And because of Japanese Street culture around Akihabara and Harajuku in the 1990s, we can trace Sephiroth‘s overall look and feel in Final Fantasy VII directly back to Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto as part of the famous Crow Tribe subculture style.

Just when we thought that everything was becoming relatable in fashion and games, and how perfect it was that there was a symbiosis of pop culture into fashion from games, accepted as the norm, cosplayed and the ante upped by technology… along came fictional space operas and zombies.

Absolutely Not Fabulous

What does anybody wear in space? Space suits mostly, and to be slightly AbFab about this, “why does everything you wear look like it’s bearing a grudge?” Japanese RPGs and action games aside, there was a distinct disconnect from the late ’90s right through the noughties where some videogame IPs had simply lost the plot in terms of fashion.

Call Jill Valentine. She’s a cop, isn’t she? In fact, we should have actually called the fashion police on Jill Valentine for everything worn in the original Resident Evil. It is frankly hideous and has not aged well. Yes, it’s a Japanese game. But it’s not a Japanese problem in the ’00s. Far from it. Games like Halo committed fashion crimes by failing to dress their characters appropriately. Yes, of course Master Chief must wear a full-on space suit. Do we really accept, however, that John-117 doesn’t have any downtime? Can someone pass him a pair of Karl Lagerfeld sweatpants? Please? And spare us Cortana and all the things she isn’t wearing. All that post-production colour grading in that questionable decade of taste took us from a place of fashionable relatability into an orange/cyan hell throughout the ’00s.

Hope sprang in the weirdest of places in the noughties. The Elder Scrolls. Bethesda Software was seemingly acutely aware of the player throughout its entire breadth of IP output. Role-playing games haven’t always carried a sense of responsibility in what the player wears in games, until The Elder Scrolls. This extra layer of awareness started cautiously at first with Arena through Daggerfall, thanks in part to modding tools, so by the time ESO and Skyrim flowed through every pore we were able to explore our identity through a variety of races and classes.

Games and fashion suddenly ceased to focus just on the character in the narrative because the player is/was the narrative. And as such the player must explore their own identity inside of this world through the aesthetic of the world and its characters. Not everyone looked the same. No one dressed the same. Okay, so if you’re a Redguard, you’re going to get issued a basic dress. But it’s this entitlement to explore everything from skin tone and eye colour to body fit that makes the strongest impact. When we add clothing and fashion to that deeply individual and intimate experience, we make what we wear into a weapon or an armour, and it becomes a design, a mechanic of the game itself. You can delve into tea chests and barrels, you can find old shoes to trade or magnificent robes to wizard in, and every single item has been thought about, designed, concepted just as it would be in a fashion house. The importance of individuality screams through The Elder Scrolls and there is literally nothing worse than going through a way shrine to find some n00b in the same obsidian armour as you (call me next time, okay?).

Zombie Nation

So Elder Scrolls is an exception to the rule of the ’00s because it was visually stunning compared to the drab world of zombies and FPS. There is no AbFab quote to describe how this whole zombie thing really did bring acceptable fashion levels down to zero, and Jill Valentine cannot be held responsible for that. Releases such as Shadow of the Colossus battled in the fashion stakes against Call of Duty 4 and Silent Hill to cut more of a dash than its other videogames counterparts. In a nutshell, the world was gunmetal grey and beige.

Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and The Sims seemed to buck the trend against studios making games that looked like used engine oil, instead taking the flamboyance of fashion to a whole new level. Kitsch fabulousness became relatable before GTA IV, and something that was relatable and close in San Andreas were definitely the types of styles that we might want to wear if we wanted to look like Little Richard, and that’s okay. These ne’er-do-wells and criminals seemed perfect and how they were styled and dressed, from Charlie Murphy’s Jizzy B to Kent Paul and Maccer, was a far cry (excuse the pun) from, erm, Far Cry and Left 4 Dead.

Like the Japanese phenomenon of immersive and connective culture and subculture, the big mood in GTA is an aesthetic built out of music, which forges that unique DNA of style. If only Guitar Hero took notes. That cultural overspill raises its head once again just as it did with the Tony Hawk’s series and today it echoes through the metaverse deadmau5’s gameworld Oberhasli. The Sims brought in the fashionable heavyweights of the time, Black Eyed Peas, to bring another pop culture aesthetic over the top of the otherwise pedestrian franchise. As The Urbz: Sims in the City, we’d finally hit that cultural/subcultural reciprocation with a bigger vibe and more comfortable wardrobe done in previous releases from Maxis.

Checkmate

This unique relationship between fashion and games appears to be at a checkmate currently. The fashion industry doesn’t play games as a rule (it shows), and games are somehow expected to up the ante of seasonal changes and challenges of fashion at large. Not so long ago I had a conversation with Maison Margiela about creating an Eve Online collection project which did little to ignite either camp.

The checkmate isn’t about anything other than technology and aspiration: on the one hand, fashion has a desire to be inside every single game but that industry’s inability and digital immaturity takes us back to crazy Zero Wing high collars. On the other, games still have a way to go to emerge from that orange-and-cyan-cocoon-drabwear of the noughties, make a decisive move out of bloodstained zombie fashion, into something that is desirable, current, attainable and sustainable.

So it’s refreshing that in this current cycle of change in technology, and as we approach this hallowed metaverse, companies like Lockwood Publishing have continued to push the agenda for how fashion (and beauty) is a communal experience in this shared persistent space for fashion and games.

Desirable, current, and attainable surely must be the direction of travel for games and fashion in 2021 and, currently, only Avakin Life has managed to do this between the digital and physical of fashion: sustainably and responsibly. Choosing to work with brands that don’t break the bank increases both appeal and demographic-centred design. The novelty aspect of Marc Jacobs in Animal Crossing and Balenciaga in Roblox only reminds us that though fashion is part of our captive identity in games yet isn’t as attainable as it easily could be, it should be, it must be, and if it isn’t part of our cultural identity does it really belong in games or the metaverse? Time will tell.

Best Dressed In Games

The criteria is that these fashions should be timeless, thorough, and well executed as per, say, Paris Fashion Week. Here are some stone-cold fashionistas:

Duke in Duke Nukem 3D (1996)

Lara Croft in Tomb Raider (1996)

James Bond in Goldeneye 007 (1997)

Solid Snake in Metal Gear Solid (1998)

Hwarang in Tekken 3 (1997)

Kaim Argonar in Lost Odyssey (2007)

Commander Shepard in Mass Effect 3 (2012)

Midna in The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (2006)

Miss Cloud in Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020)

Call The Fashion Police

If you need an explanation, think about your geography teacher at a high school disco. It’s a ‘no’ from all of us. From drab colours to ill-fitting designs, here are some faux pas:

Nathan Drake in Uncharted (2007)

Crazy Pizza in Enchanted Arms (2006)

Jill Valentine in Resident Evil (1996)

Ivy in Soul Calibur (1998)

Lynch in Kane & Lynch (2007)

Zarya in Overwatch (2016)

Dagoth Ur in The Elder Scrolls 3: Morrowind (2002)

Princess Peach in Super Mario (1985)

Randy Tugman in Dead Rising 2 (2010)

Kelly lives and breathes everything Beyond Games as a futurist and self-described creative badass. And as an experienced game developer, she's worked on titles such as Tomb Raider, Halo 3 and Candy Crush.